Shallow Thoughts : tags : hardware

Akkana's Musings on Open Source Computing and Technology, Science, and Nature.

Fri, 19 Dec 2025

![[A sensor and small microcontroller, connected by a cable, sitting on pink anti-static bubblewrap. The microcontroller is also plugged in to a USB cable and a battery; it has a built-in display that reads: CO2: 470 ppm, Temp: 77F, Hum: 18%, BAT 65%]](https://shallowsky.com/blog/images/hardware/airCO2/PXL_20251202_161750086T.jpg) Despite most of the world deciding that COVID is over, I continue to

be cautious about it. (My one bout of COVID resulted in congestive heart

failure which I'm still dealing with, so I'm fairly anxious not to get it again.)

Despite most of the world deciding that COVID is over, I continue to

be cautious about it. (My one bout of COVID resulted in congestive heart

failure which I'm still dealing with, so I'm fairly anxious not to get it again.)

That means that I'm cautious about indoor gatherings. Some places say

they've upgraded their ventilation, but can you believe them?

I've long read about people using CO2 meters as a proxy, to tell you how

well the air is circulating and how high the virus load might be in a crowd,

and I've wanted to get one of my own.

You can buy CO2 meters, of course. But making a custom one sounds so much

more fun! Reading Wired's story about

New Zealand's Kawaiicon cybersecurity convention

that provided CO2 trackers

inspired me to finally order some parts.

Read more ...

Tags: maker, hardware, python, circuitpython

[

18:06 Dec 19, 2025

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Sun, 14 Dec 2025

(With a cheap imperfect tool)

![[a box with compartments for several sizes of small white connectors, plus one compartment filled with little metal pieces]](https://shallowsky.com/blog/images/hardware/jst-crimp/PXL_20251209_203457520.jpg) I've written about the several neat boards I recently ordered from Adafruit.

I've written about the several neat boards I recently ordered from Adafruit.

But when I ordered,

I was confused about which connectors were which, and didn't end up

ordering all the connectors I needed.

Adafruit calls the connectors they use "Stemma", and (I realized too late)

they have a helpful page called

What is Stemma?

explaining the different connectors.

I had ordered several of the small ones, "Stemma QT",

more technically a 4 Pin JST SH, which were perfect for connecting a

Feather board to a CO2 meter.

But I hadn't realized that the bigger board, the PyPortal,

needs a larger connector also called Stemma,

more technically a JST PH.

It turned out to be hard to find JST PH connectors with wires already

attached ("pigtails") and what I found were impressively expensive in

lots of two or three. I imagine I might want a fair number of JST PH,

especially the 2-connector type used for batteries.

So I ordered a boxed assortment of 2, 3 and 4-pin JST PH connectors

and a crimp tool.

Read more ...

Tags: hardware, maker, electronics

[

13:34 Dec 14, 2025

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Tue, 09 Dec 2025

(On Linux.)

![[a microcontroller the size of a qyarter, plugged in to a light string wound through a blue knit cap]](https://shallowsky.com/blog/images/hardware/circuitpy/PXL_20251208_191544313.jpg) I wrote previously about my difficulties

installing

CircuitPython on an ESP32 Feather.

I wrote previously about my difficulties

installing

CircuitPython on an ESP32 Feather.

When I ordered the Feather, I ordered a bunch of other stuff too, including

a tiny wearable microcontroller that's sold specifically for MicroPython: a

Gemma M0.

Again, I had trouble getting MicroPython working, but the Gemma's problem

was quite different.

Read more ...

Tags: hardware, python, circuitpython

[

18:13 Dec 09, 2025

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Thu, 04 Dec 2025

![[A small microcontroller with a built-in display reading CO2: 470ppm and some other stuff, plugged into a USB-C cable]](https://shallowsky.com/blog/images/hardware/PXL_20251202_161750086c.jpg)

(On Linux, natch.)

I've been wanting to play around with

CircuitPython for ages.

I like Python, I like microcontrollers, what's not to like?

Quite a while back, I even ordered a Feather M0 for that — but I

didn't do my research, ordered the wi-fi version and it turned out that's

the one Feather M0 that can't run CircuitPython.

This time I checked more carefully before ordering, and got a

processor that for sure claimed to run CircuitPython.

Read more ...

Tags: hardware, python, circuitpython, maker

[

13:58 Dec 04, 2025

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Fri, 17 Aug 2018

Over the years I've picked up a couple of cellphone stands as

conference giveaways. A stand is a nice idea, especially if you

like to read news articles during mealtime, but the stands I've

tried never seem to be quite what I want. Either they're not

adjustable, or they're too bulky or heavy to want to carry them

around all the time.

A while back, I was browsing on ebay looking for something better

than the ones I have. I saw a few that looked like they might be

worth trying, but then it occurred to me: I could make one pretty

easily that would work better than anything I'd found for sale.

I started with plans that involved wire and a hinge -- the hinge so

the two sides of the stand would fold together to fit in a purse or

pocket -- and spent a few hours trying different hinge options.I

wasn't satisfied, though. And then I realized: all I had to do was

bend the wire into the shape I needed. Voilà -- instant

lightweight adjustable cellphone stand.

And it has worked great. I've been using it for months and it's much

better than any of the prefab stands I had before.

Bend a piece of wire

![[Bent wire]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/cellphone-stand/img_2635.jpg)

I don't know where this wire came from: it was in my spare-metal-parts

collection. You want something a little thinner than coathanger wire,

so you can bend it relatively easily; "baling wire" or "rebar wire"

is probably about right.

Bend the tips around

![[Tips adjusted to fit your phone's width]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/cellphone-stand/img_2638.jpg)

Adjust the curve so it's big enough that your cellphone will fit in

the crook of the wires.

Bend the back end down, and spread the two halves apart

![[Bend the back end down]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/cellphone-stand/img_2639.jpg)

Adjust so it fits your phone

![[Instant cellphone stand]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/cellphone-stand/img_2640.jpg)

Coat the finished stand with rubberized coating (available at

your local hardware store in either dip or spray-on varieties)

so it won't slide around on tables and won't scratch anything.

The finished product is adjustable to any angle you need -- so you

can adjust it based on the lighting in any room -- and you can fold

the two halves together to make it easy to carry.

Tags: hardware, hack, maker

[

12:06 Aug 17, 2018

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Sat, 10 Mar 2018

![[Intel Galileo Gen2 by Mwilde2 on Wikimedia commons]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/IntelGalileoGen2.png/320px-IntelGalileoGen2.png) Our makerspace got a donation of a bunch of Galileo gen2 boards from Intel

(image

from Mwilde2

on Wikimedia commons).

Our makerspace got a donation of a bunch of Galileo gen2 boards from Intel

(image

from Mwilde2

on Wikimedia commons).

The Galileo line has been discontinued, so there's no support and

no community, but in theory they're fairly interesting boards.

You can use a Galileo in two ways: you can treat it

like an Arduino, after using the Arduino IDE to download a

Galileo hardware definition since they're not Atmega chips. They

even have Arduino-format headers so you can plug in an Arduino shield.

That works okay (once you figure out that you need to download

the Galileo v2 hardware definitions, not the regular Galileo).

But they run Linux under the hood, so you can also use them as a

single-board Linux computer.

Serial Cable

The first question is how to talk to the board. The documentation is terrible,

and web searches aren't much help because these boards were never

terribly popular. Worse, the v1 boards seem to have been more widely

adopted than the v2 boards, so a lot of what you find on the web

doesn't apply to v2. For instance, the v1 required a special serial cable

that used a headphone jack as its connector.

Some of the Intel documentation talks about how you can load a special

Arduino sketch that then disables the Arduino bootloader and instead

lets you use the USB cable as a serial monitor. That made me nervous:

once you load that sketch, Arduino mode no longer works until you

run a command on Linux to start it up again. So if the sketch doesn't

work, you may have no way to talk to the Galileo.

Given the state of the documentation I'd already struggled with for

Arduino mode, it didn't sound like a good gamble. I thought a real

serial cable sounded like a better option.

Of course, the Galileo documentation doesn't tell you what needs to

plug in where for a serial cable. The board does have a standard FTDI

6-pin header on the board next to the ethernet jack, and the labels on

the pins seemed to correspond to the standard pinout on my Adafruit

FTDI Friend: Gnd, CTS, VCC, TX, RX, RTS. So I tried that first, using

GNU screen to connect to it from Linux just like I would a Raspberry

Pi with a serial cable:

screen /dev/ttyUSB0 115200

Powered up the Galileo and sure enough, I got boot messages and was

able to log in as root with no password. It annoyingly forces orange

text on a black background, making it especially hard to read on

a light-background terminal, but hey, it's a start.

Later I tried a Raspberry Pi serial cable, with just RX (green), TX (white)

and Gnd (black) -- don't use the red VCC wire since the Galileo is already

getting power from its own power brick -- and that worked too. The Galileo

doesn't actually need CTS or RTS. So that's good: two easy ways to talk to

the board without buying specialized hardware. Funny they didn't bother

to mention it in the docs.

Blinking an LED from the Command Line

Once connected, how do you do anything? Most of the

Intel

tutorials on Linux are useless, devoting most of their space

to things like how to run Putty on Windows and no space at all to

how to talk to pins. But I finally found a

discussion thread

with a Python example for Galileo. That's not immediately helpful

since the built-in Linux doesn't have python installed (nor gcc,

natch). Fortunately, the Python example used files in /sys

rather than a dedicated Python library;

we can access /sys files just as well from the shell.

Of course, the first task is to blink an LED on pin 13. That

apparently corresponds to GPIO 7 (what are the other arduino/GPIO

correspondences? I haven't found a reference for that yet.) So you

need to export that pin (which creates /sys/class/gpio/gpio7

and set its direction to out. But that's not enough: the

pin still doesn't turn on when you

echo 1 > /sys/class/gpio/gpio7/value. Why not?

I don't know, but the Python script exports three other pins --

46, 30, and 31 -- and echoes 0 to 30 and 31. (It does this without

first setting their directions to out, and if you try

that, you'll get an error, so I'm not convinced the Python script

presented as the "Correct answer" would actually have worked. Be warned.)

Anyway, I ended up with these shell lines as

preparation before the Galileo can actually blink:

# echo 7 >/sys/class/gpio/export

# echo out > /sys/class/gpio/gpio7/direction

# echo 46 >/sys/class/gpio/export

# echo 30 >/sys/class/gpio/export

# echo 31 >/sys/class/gpio/export

# echo out > /sys/class/gpio/gpio30/direction

# echo out > /sys/class/gpio/gpio31/direction

# echo 0 > /sys/class/gpio/gpio30/value

# echo 0 > /sys/class/gpio/gpio31/value

And now, finally, you can control the LED on pin 13 (GPIO 7):

# echo 1 > /sys/class/gpio/gpio7/value

# echo 0 > /sys/class/gpio/gpio7/value

or run a blink loop:

# while /bin/true; do

> echo 1 > /sys/class/gpio/gpio7/value

> sleep 1

> echo 0 > /sys/class/gpio/gpio7/value

> sleep 1

> done

Searching Fruitlessly for a "Real" Linux Image

All the Galileo documentation is emphatic that you should download

a Linux distro and burn it to an SD card rather than using the Yocto

that comes preinstalled. The preinstalled Linux apparently has no

persistent storage, so not only does it not save your Linux programs,

it doesn't even remember the current Arduino sketch.

And it has no programming languages and only a rudimentary busybox shell.

So finding and downloading a Linux distro was the next step.

Unfortunately, that mostly led to dead ends. All the official Intel

docs describe different download filenames, and they all point to

generic download pages that no longer include any of the filenames

mentioned. Apparently Intel changed the name for its Galileo images

frequently and never updated its documentation.

After forty-five minutes of searching and clicking around,

I eventually found my way to

Intel® IoT Developer Kit Installer Files,

which includes sizable downloads with names like

- iss-iot-linux_12-09-16.tar.bz2 (324.07 MB),

- intel-iot-yocto.tar.xz (147.53 MB),

- intel-iot-wrs-pulsar-64.tar.xz (283.86 MB),

- intel-iot-wrs-32.tar.xz (386.16 MB), and

- intel-iot-ubuntu.tar.xz (209.44 MB)

From the size, I suspect those are all Linux images. But what are they

and how do they differ? Do any of them still have working repositories?

Which ones come with Python, with gcc, with GPIO support,

with useful development libraries? Do any of them get security updates?

As far as I can tell, the only way to tell is to download each image,

burn it to a card, boot from it, then explore the filesystem

trying to figure out what distro it is and how to try updating it.

But by this time I'd wasted three hours and gotten no

further than the shell commands to blink a single LED, and I ran out of

enthusiasm. I mean, I could spend five more hours on this, try several

of the Linux images, and see which one works best. Or I could spend

$10 on a Raspberry Pi Zero W that has abundant documentation,

libraries, books, and community howtos. Plus wi-fi, bluetooth and HDMI,

none of which the Galileo has.

Arduino and Linux Living Together

So that's as far as I've gone. But I do want to note

one useful thing I stumbled upon while searching

for information about Linux distributions:

Starting Arduino

sketch from Linux terminal shows how to run an Arduino sketch

(assuming it's already compiled) from Linux:

sketch.elf /dev/ttyGS0 &

It's a fairly cool option to have. Maybe one of these days, I'll pick

one of the many available distros and try it.

Tags: hardware, linux, intel, galileo, arduino, maker

[

13:54 Mar 10, 2018

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Sat, 17 Feb 2018

In the previous article I talked about

Multiplexing

input/output using shift registers for a music keyboard project.

I ended up with three CD4021 8-bit shift registers cascaded.

It worked; but I found that I was spending all my time in the

delays between polling each bit serially. I wanted a way to read

those bits faster. So I ordered some I/O expander chips.

![[Keyboard wired to Raspberry Pi with two MCP23017 port expanders]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/multiplex/img_1995.jpg) I/O expander, or port expander, chips take a lot of the hassle out of

multiplexing. Instead of writing code to read bits serially, you can use I2C.

Some chips also have built-in pullup resistors, so you don't need all

those extra wires for pullups or pulldowns.

There are lots of options, but two common chips are the MCP23017,

which controls 16 lines, and the MCP23008 and PCF8574p, which each

handle 8. I'll only discuss the MCP23017 here, because if eight is good,

surely sixteen is better! But the MCP23008 is basically the same thing

with fewer I/O lines.

I/O expander, or port expander, chips take a lot of the hassle out of

multiplexing. Instead of writing code to read bits serially, you can use I2C.

Some chips also have built-in pullup resistors, so you don't need all

those extra wires for pullups or pulldowns.

There are lots of options, but two common chips are the MCP23017,

which controls 16 lines, and the MCP23008 and PCF8574p, which each

handle 8. I'll only discuss the MCP23017 here, because if eight is good,

surely sixteen is better! But the MCP23008 is basically the same thing

with fewer I/O lines.

A good tutorial to get you started is

How

To Use A MCP23017 I2C Port Expander With The Raspberry Pi - 2013 Part 1

along

with part

2, Python and

part

3, reading input.

I'm not going to try to repeat what's in those tutorials, just

fill in some gaps I found. For instance,

I didn't find I needed sudo for all those I2C commands in Part 1

since my user is already in the i2c group.

Using Python smbus

Part 2 of that tutorial uses Python smbus, but it doesn't really

explain all the magic numbers it uses, so it wasn't obvious how to

generalize it when I added a second expander chip. It uses this code:

DEVICE = 0x20 # Device address (A0-A2)

IODIRA = 0x00 # Pin direction register

OLATA = 0x14 # Register for outputs

GPIOA = 0x12 # Register for inputs

# Set all GPA pins as outputs by setting

# all bits of IODIRA register to 0

bus.write_byte_data(DEVICE,IODIRA,0x00)

# Set output all 7 output bits to 0

bus.write_byte_data(DEVICE,OLATA,0)

DEVICE is the address on the I2C bus, the one you see with

i2cdetect -y 1 (20, initially).

IODIRA is the direction: when you call

bus.write_byte_data(DEVICE, IODIRA, 0x00)

you're saying that all eight bits in GPA should be used for output.

Zero specifies output, one input: so if you said

bus.write_byte_data(DEVICE, IODIRA, 0x1F)

you'd be specifying that you want to use the lowest five bits for output

and the upper three for input.

OLATA = 0x14 is the command to use when writing data:

bus.write_byte_data(DEVICE, OLATA, MyData)

means write data to the eight GPA pins. But what if you want to write to

the eight GPB pins instead? Then you'd use

OLATB = 0x15

bus.write_byte_data(DEVICE, OLATB, MyData)

Likewise, if you want to read input from some of the GPB bits, use

GPIOB = 0x13

val = bus.read_byte_data(DEVICE, GPIOB)

The MCP23017 even has internal pullup resistors you can enable:

GPPUA = 0x0c # Pullup resistor on GPA

GPPUB = 0x0d # Pullup resistor on GPB

bus.write_byte_data(DEVICE, GPPUB, inmaskB)

Here's a full example:

MCP23017.py

on GitHub.

Using WiringPi

You can also talk to an MCP23017 using the WiringPi library.

In that case, you don't set all the bits at once, but instead treat

each bit as though it were a separate pin. That's easier to think

about conceptually -- you don't have to worry about bit shifting

and masking, just use pins one at a time -- but it might be slower

if the library is doing a separate read each time you ask for an input bit.

It's probably not the right approach to use if you're trying to check

a whole keyboard's state at once.

Start by picking a base address for the pin number -- 65 is the lowest

you can pick -- and initializing:

pin_base = 65

i2c_addr = 0x20

wiringpi.wiringPiSetup()

wiringpi.mcp23017Setup(pin_base, i2c_addr)

Then you can set input or output mode for each pin:

wiringpi.pinMode(pin_base, wiringpi.OUTPUT)

wiringpi.pinMode(input_pin, wiringpi.INPUT)

and then write to or read from each pin:

wiringpi.digitalWrite(pin_no, 1)

val = wiringpi.digitalRead(pin_no)

WiringPi also gives you access to the MCP23017's internal pullup resistors:

wiringpi.pullUpDnControl(input_pin, 2)

Here's an example in Python:

MCP23017-wiringpi.py

on GitHub, and one in C:

MCP23017-wiringpi.c

on GitHub.

Using multiple MCP23017s

But how do you cascade several MCP23017 chips?

Well, you don't actually cascade them. Since they're I2C

devices, you wire them so they each have different addresses on the

I2C bus, then query them individually. Happily, that's

easier than keeping track of how many bits you've looped through ona

shift register.

Pins 15, 16 and 17 on the chip are the address lines, labeled A0, A1

and A2. If you ground all three you get the base address of 0x20.

With all three connected to VCC, it will use 0x27 (binary 111 added to

the base address). So you can send commands to your first device at 0x20,

then to your second one at 0x21 and so on. If you're using WiringPi,

you can call mcp23017Setup(pin_base2, i2c_addr2) for your second chip.

I had trouble getting the addresses to work initially, and it turned

out the problem wasn't in my understanding of the address line wiring,

but that one of my cheap Chinese breadboard had a bad power and ground

bus in one quadrant. That's a good lesson for the future: when things

don't work as expected, don't assume the breadboard is above suspicion.

Using two MCP23017 chips with their built-in pullup resistors simplified

the wiring for my music keyboard enormously, and it made the code

cleaner too. Here's the modified code:

keyboard.py

on GitHub.

What about the speed? It is indeed quite a bit faster than the shift

register code. But it's still too laggy to use as a real music keyboard.

So I'll still need to do more profiling, and maybe find a faster way

of generating notes, if I want to play music on this toy.

Tags: hardware, raspberry pi, python, maker

[

15:44 Feb 17, 2018

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Tue, 13 Feb 2018

I was scouting for parts at a thrift shop and spotted a little

23-key music keyboard. It looked like a fun Raspberry Pi project.

I was hoping it would turn out to use some common protocol like I2C,

but when I dissected it, it turned out there was a ribbon cable with

32 wires coming from the keyboard. So each key is a separate pushbutton.

![[23-key keyboard wired to a Raspberry Pi]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/multiplex/img_1986-640.jpg) A Raspberry Pi doesn't have that many GPIO pins, and neither does an

Arduino Uno. An Arduino Mega does, but buying a Mega to go between the

Pi and the keyboard kind of misses the point of scavenging a $3 keyboard;

I might as well just buy an I2C or MIDI keyboard. So I needed some sort

of I/O multiplexer that would let me read 31 keys using a lot fewer pins.

A Raspberry Pi doesn't have that many GPIO pins, and neither does an

Arduino Uno. An Arduino Mega does, but buying a Mega to go between the

Pi and the keyboard kind of misses the point of scavenging a $3 keyboard;

I might as well just buy an I2C or MIDI keyboard. So I needed some sort

of I/O multiplexer that would let me read 31 keys using a lot fewer pins.

There are a bunch of different approaches to multiplexing. A lot of

keyboards use a matrix approach, but that makes more sense when you're

wiring up all the buttons from scratch, not starting with a pre-wired

keyboard like this. The two approaches I'll discuss here are

shift registers and multiplexer chips.

If you just want to get the job done in the most efficient way,

you definitely want a multiplexer (port expander) chip, which I'll

cover in Part 2. But for now, let's look at the old-school way: shift

registers.

PISO Shift Registers

There are lots of types of shift registers, but for reading lots of inputs,

you need a PISO shift register: "Parallel In, Serial Out."

That means you can tell the chip to read some number -- typically 8 --

of inputs in parallel, then switch into serial mode and read all the bits

one at a time.

Some PISO shift registers can cascade: you can connect a second shift

register to the first one and read twice as many bits. For 23 keys

I needed three 8-bit shift registers.

Two popular cascading PISO shift registers are the CD4021 and the SN74LS165.

They work similarly but they're not exactly the same.

The basic principle with both the CD4021 and the SN74LS165:

connect power and ground, and wire up all your inputs to the eight data pins.

You'll need pullup or pulldown resistors on each input line, just like

you normally would for a pushbutton; I recommend picking up a few

high-value (like 1-10k) resistor arrays: you can get these in SIP

(single inline package) or DIP (dual-) form factors that plug easily

into a breadboard. Resistor arrays can be either independent

two pins for each resistor in the array) or bussed (one pin in

the chip is a common pin, which you wire to ground for a pulldown or

V+ for a pullup; each of the rest of the pins is a resistor). I find

bussed networks particularly handy because they can reduce the number

of wires you need to run, and with a job where you're multiplexing

lots of lines, you'll find that getting the wiring straight is a big

part of the job. (See the photo above to see what a snarl this was

even with resistor networks.)

For the CD4021, connect three more pins: clock and data pins (labeled

CLK and either Q7 or Q8 on the chip's pinout, pins 10 and 3),

plus a "latch" pin (labeled M, pin 9).

For the SN74LS165, you need one more pin: you need clock and data

(labeled CP and Q7, pins 2 and 9), latch (labeled

PL, pin 1),

and clock enable (labeled CE,

pin 15).

At least for the CD4021, some people

recommend

a 0.1 uF bypass capacitor across the power/ground connections of each

CD4021.

If you need to cascade several chips with the CD4021, wire DS (pin 11)

from the first chip to Q7 (pin 3), then wire both chips clock lines together

and both chips' data lines together. The SN74LS165 is the same: DS

(pin 10) to Q8 (pin 9) and tie the clock and data lines together.

Once wired up, you toggle the latch to read the parallel data, then

toggle it again and use the clock pin to read the series of bits.

You can see the specific details in my Python scripts:

CD4021.py

on GitHub and

SN74LS165.py

on GitHub.

Some References

For wiring diagrams, more background, and Arduino code for the CD4021, read

Arduino

ShiftIn.

For the SN74LS165, read:

Arduino:

SN74HC165N,

74HC165 8 bit Parallel in/Serial out Shift Register,

or Sparkfun:

Shift Registers.

Of course, you can use a shift register for output as well as input.

In that case you need a SIPO (Serial In, Parallel Out) shift register

like a 74HC595. See

Arduino ShiftOut:

Serial to Parallel Shifting-Out with a 74HC595

Interfacing

74HC595 Serial Shift Register with Raspberry Pi.

Another, less common option is the 74HC164N:

Using

a SN74HC164N Shift Register With Raspberry Pi

For input from my keyboard, initially I used three CD4021s. It basically worked,

and you can see the code for it at

keyboard.py

(older version, for CD4021 shift registers), on GitHub.

But it turned out that looping over all those bits was slow -- I've

been advised that you should wait at least 25 microseconds between

bits for the CD4021, and even at 10 microseconds I found there wasa

significant delay between hitting the key and hearing the note.I

thought it might be all the fancy numpy code to generate waveforms for

the chords, but when I used the Python profiler, it said most of the

program's time was taken up in time.sleep(). Fortunately, there's a

faster solution than shift registers: port expanders, which I'll talk

about in Multiplexing Part 2: Port Expanders.

Tags: hardware, raspberry pi, python, maker

[

12:23 Feb 13, 2018

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Sun, 21 Jan 2018

When you attach hardware buttons to a Raspberry Pi's GPIO pin,

reading the button's value at any given instant is easy with

GPIO.input(). But what if you want to watch for

button changes? And how do you do that from a GUI program where

the main loop is buried in some library?

Here are some examples of ways to read buttons from a Pi.

For this example, I have one side of my button wired to the Raspberry

Pi's GPIO 18 and the other side wired to the Pi's 3.3v pin.

I'll use the Pi's internal pulldown resistor rather than adding

external resistors.

The simplest way: Polling

The obvious way to monitor a button is in a loop, checking the

button's value each time:

import RPi.GPIO as GPIO

import time

button_pin = 18

GPIO.setmode(GPIO.BCM)

GPIO.setup(button_pin, GPIO.IN, pull_up_down = GPIO.PUD_DOWN)

try:

while True:

if GPIO.input(button_pin):

print("ON")

else:

print("OFF")

time.sleep(1)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("Cleaning up")

GPIO.cleanup()

But if you want to be doing something else while you're waiting,

instead of just sleeping for a second, it's better to use edge detection.

Edge Detection

GPIO.add_event_detect,

will call you back whenever it sees the pin's value change.

I'll define a button_handler function that prints out

the value of the pin whenever it gets called:

import RPi.GPIO as GPIO

import time

def button_handler(pin):

print("pin %s's value is %s" % (pin, GPIO.input(pin)))

if __name__ == '__main__':

button_pin = 18

GPIO.setmode(GPIO.BCM)

GPIO.setup(button_pin, GPIO.IN, pull_up_down = GPIO.PUD_DOWN)

# events can be GPIO.RISING, GPIO.FALLING, or GPIO.BOTH

GPIO.add_event_detect(button_pin, GPIO.BOTH,

callback=button_handler,

bouncetime=300)

try:

time.sleep(1000)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

GPIO.cleanup()

Pretty nifty. But if you try it, you'll probably find that sometimes

the value is wrong. You release the switch but it says the value is

1 rather than 0. What's up?

Debounce and Delays

The problem seems to be in the way RPi.GPIO handles that

bouncetime=300 parameter.

The bouncetime is there because hardware switches are noisy. As you

move the switch from ON to OFF, it doesn't go cleanly all at once

from 3.3 volts to 0 volts. Most switches will flicker back

and forth between the two values before settling down. To see bounce

in action, try the program above without the bouncetime=300.

There are ways of fixing bounce in hardware, by adding a capacitor or

a Schmitt trigger to the circuit; or you can "debounce" the button

in software, by waiting a while after you see a change before

acting on it. That's what the bouncetime parameter is for.

But apparently RPi.GPIO, when it handles bouncetime, doesn't

always wait quite long enough before calling its event function.

It sometimes calls button_handler while the switch is still

bouncing, and the value you read might be the wrong one.

Increasing bouncetime doesn't help.

This seems to be a bug in the RPi.GPIO library.

You'll get more reliable results if you wait a little while before

reading the pin's value:

def button_handler(pin):

time.sleep(.01) # Wait a while for the pin to settle

print("pin %s's value is %s" % (pin, GPIO.input(pin)))

Why .01 seconds? Because when I tried it, .001 wasn't enough, and if

I used the full bounce time, .3 seconds (corresponding to 300 millisecond

bouncetime), I found that the button handler

sometimes got called multiple times with the wrong value. I wish

I had a better answer for the right amount of time to wait.

Incidentally, the choice of 300 milliseconds for bouncetime is arbitrary

and the best value depends on the circuit. You can play around with

different values (after commenting out the .01-second sleep) and

see how they work with your own circuit and switch.

You might think you could solve the problem by using two handlers:

GPIO.add_event_detect(button_pin, GPIO.RISING, callback=button_on,

bouncetime=bouncetime)

GPIO.add_event_detect(button_pin, GPIO.FALLING, callback=button_off,

bouncetime=bouncetime)

but that apparently isn't allowed:

RuntimeError: Conflicting edge detection already enabled for

this GPIO channel.

Even if you look just for GPIO.RISING, you'll

still get some bogus calls, because there are both rising and falling

edges as the switch bounces. Detecting GPIO.BOTH, waiting

a short time and checking the pin's value is the only reliable method

I've found.

Edge Detection from a GUI Program

And now, the main inspiration for all of this: when you're running a

program with a graphical user interface, you don't have

control over the event loop. Fortunately, edge detection works

fine from a GUI program. For instance, here's a simple TkInter program

that monitors a button and shows its state.

import Tkinter

from RPi import GPIO

import time

class ButtonWindow:

def __init__(self, button_pin):

self.tkroot = Tkinter.Tk()

self.tkroot.geometry("100x60")

self.label = Tkinter.Label(self.tkroot, text="????",

bg="black", fg="white")

self.label.pack(padx=5, pady=10, side=Tkinter.LEFT)

self.button_pin = button_pin

GPIO.setmode(GPIO.BCM)

GPIO.setup(self.button_pin, GPIO.IN, pull_up_down=GPIO.PUD_DOWN)

GPIO.add_event_detect(self.button_pin, GPIO.BOTH,

callback=self.button_handler,

bouncetime=300)

def button_handler(self, channel):

time.sleep(.01)

if GPIO.input(channel):

self.label.config(text="ON")

self.label.configure(bg="red")

else:

self.label.config(text="OFF")

self.label.configure(bg="blue")

if __name__ == '__main__':

win = ButtonWindow(18)

win.tkroot.mainloop()

You can see slightly longer versions of these programs in my

GitHub

Pi Zero Book repository.

Tags: hardware, raspberry pi, programming, python, maker

[

11:32 Jan 21, 2018

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Sat, 16 Dec 2017

Playing with the

ATtiny85

I was struck by how simple the circuit was.

Sure, I'd made a

homemade

Arduino on a breadboard;

but with the crystal and all the extra capacitors and resistors it ends

up seeming like a lot of parts and wires.

If an ATtiny can use a built-in clock and not need all those extra

parts, couldn't I use an Atmega328 the same way?

![[Circuit for Atmega328 on breadboard with ISP]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/arduino/bare-atmega-breadboard-isp_bb.jpg) Why, yes, as it turns out. But there are a few tricks.

Why, yes, as it turns out. But there are a few tricks.

Wire it

Wiring a bare Atmega chip is easy.

You'll want to keep a good pinout diagram handy, like this

Arduino

ATmega328 Pinout from HobbyTronics.

For the initial wiring, all you need is

two power and two ground lines, the pins marked - and +,

plus a pullup resistor on RST (something large, like 10kΩ).

The excellent tutorial

From

Arduino to a Microcontroller on a Breadboard is a good guide

if you need additional details: the third section

shows a circuit without external clock.

Add an LED and resistor on pin 13 (atmega pin 19, called SCK) so

you can test it using a blink program.

Now you need to set up the software.

Set up a hardware profile for a bare Arduino

To program it with the Arduino libraries,

you'll need a hardware definition for an atmega328 chip

with an internal clock. I used the download

from the last section of the excellent tutorial,

From

Arduino to a Microcontroller on a Breadboard. (Keep that page

up: it has good wiring diagrams.)

For Arduino 1.8.5, download breadboard-1-6-x.zip and unpack it

in your ~/sketchbook/hardware/ directory, making a directory

there called breadboard. Then you'll need to make one change:

the 1.6 directory is missing a file called pins_arduino.h",

so if you try to compile with this hardware definition, you'll get

an error like:

mkdir -p build-atmega328bb-atmega328

/usr/local/share/arduino/hardware/tools/avr/bin/avr-g++ -x c++ -include Arduino.h -MMD -c -mmcu=atmega328p -DF_CPU=8000000L -DARDUINO=185 -DARDUINO_ARCH_AVR -D__PROG_TYPES_COMPAT__ -I/usr/local/share/arduino/hardware/arduino/avr/cores/arduino -I/home/akkana/sketchbook/hardware/breadboard/avr/variants/standard -Wall -ffunction-sections -fdata-sections -Os -fpermissive -fno-exceptions -std=gnu++11 -fno-threadsafe-statics -flto blink.ino -o build-atmega328bb-atmega328/blink.ino.o

In file included from :0:0:

/usr/local/share/arduino/hardware/arduino/avr/cores/arduino/Arduino.h:257:26: fatal error: pins_arduino.h: No such file or directory

#include "pins_arduino.h"

^

compilation terminated.

/usr/share/arduino/Arduino.mk:1251: recipe for target 'build-atmega328bb-atmega328/blink.ino.o' failed

make: *** [build-atmega328bb-atmega328/blink.ino.o] Error 1

The problem is that it's including these directories:

-I/usr/local/share/arduino/hardware/arduino/avr/cores/arduino

-I/home/akkana/sketchbook/hardware/breadboard/avr/variants/standard

but the actual file is in:

/usr/local/share/arduino/hardware/arduino/avr/variants/standard/pins_arduino.h

You can fix that by making a link from the "standard" directory in your

Arduino install to breadboard/avr/variants/standard. On Linux, that would

be something like this (Mac and Windows people can substitute their

local equivalents):

ln -s /usr/local/share/arduino/hardware/arduino/avr/variants/standard ~/sketchbook/hardware/breadboard/avr/variants/

Now your hardware definition should be ready to go. To check, fire up

the IDE and look in Tools->Board for

ATmega328 on a breadboard (8 MHz internal clock).

Or if you use Arduino-mk, run

ALTERNATE_CORE=breadboard make show_boards

and make sure it lists

atmega328bb ATmega328 on a breadboard (8 MHz internal clock).

Reprogram the Fuses and Bootloader for an Internal Clock

The next trick is that an Atmega chip programmed with the Arduino

bootloader is also fused to use an external, 16MHz clock.

If you wire it to use its internal 8MHz clock, you won't be

able to talk to it with either an ISP or FTDI.

You'll definitely run into this if you pull the CPU out of an Arduino.

But even if you buy new chips you may see it:

many Atmega328s come pre-programmed with the Arduino bootloader.

After all, that's what most people want.

The easiest way to reprogram the fuses is to use the hardware

definition you just installed to burn a new bootloader, which resets

the fuse settings at the same time. So you need an In-System

Programmer, or ISP. You can use an Arduino as an ISP, but I'm told

that this tends to be flaky and isn't recommended. After I had

problems using an Arduino I ordered a cheap USBtinyUSP, which works

fine.

Regardless of which ISP you use, if you wire up your atmega without

an external clock when it's fused for one, you won't be able to burn a

bootloader. A typical error:

[ ... ]

Reading | ################################################## | 100% 0.02s

avrdude: Device signature = 0x000000 (retrying)

Error while burning bootloader.

Reading | ################################################## | 100% 0.02s

avrdude: Device signature = 0x000000

avrdude: Yikes! Invalid device signature.

Double check connections and try again, or use -F to override

this check.

The solution is to burn the bootloader using an external clock.

You can add a crystal and two capacitors to your breadboard circuit

if you have them.

If not, an easy solution is to pull the chip out of the breadboard,

plug it into the socket in an Arduino and burn it there.

(Note: if you're using an Arduino as your ISP, you'll need a second

Arduino.)

Plug your ISP into the Arduino's ISP header: on an Uno, that's the

header labeled ICSP at the end of the chip farthest away from the USB

plug. It's a six-pin connector (2x3), it's easy to plug in backward

and you can't depend on either the Arduino's header or the ISP's cable

being labeled as to direction; if in doubt, use a multimeter in

continuity mode to see which pin is ground on each side, then make

sure those pins match. Once you're sure, mark your connector somehow

so you'll know next time.

In the Arduino IDE, set Tools->Board to

ATmega328 on a breadboard (8 MHz internal clock),

set Programmer to whatever ISP you're using.

then run Tools->Burn Bootloader.

If you're using Arduino-mk instead of the IDE,

set up a Makefile that looks like this:

ALTERNATE_CORE = breadboard

BOARD_TAG = atmega328bb

ISP_PROG = usbtiny

include /usr/local/share/Arduino-Makefile/Arduino.mk

Substitute your ISP, if different, and your location for Arduino.mk.

Then type

make burn_bootloader

Program it

Once you're wired, you should be able to program it either with an

FTDI board or an ISP, as I discussed in

homemade

Arduino, Part 1.

You should be able to use your minimal Atmega328 to

run anything you can run on a normal Arduino (albeit at half the

clock speed).

I plan to make a little board with a ZIF socket and connectors for

both the USBtinyISP and the FTDI Friend so I don't have to plug in

all those wires again each time.

Tags: hardware, arduino, maker

[

13:14 Dec 16, 2017

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Sat, 09 Dec 2017

There are lots of tutorials around for building an Arduino on a

breadboard, using an Atmega328 (or the older 168) chip, a crystal,

a few capacitors and resistors and a power supply.

It's a fun project that every Arduino hacker should try at least once.

But while there are lots of instructions on how to wire up a breadboard

Arduino, most instructions on how to program one are confusing and incomplete.

Of course, you can program your Atmega chip while it's in an Arduino,

then unplug it from the Arduino's socket and move it to the

breadboard. But what a hassle! It's so more convenient to leave the chip

in the breadboard while you test new versions of the code. And you can,

in two different ways: with FTDI, which uses the Arduino bootloader,

or with an ISP, which doesn't.

Either way, start by downloading a good pinout diagram for the

Atmega328 chip. I use this one: the

Arduino

ATmega328 Pinout from HobbyTronics, which is very compact yet does a

good job of including both the mappings to Arduino digital and analog

pins and the functions like RX, TX, MOSI and MISO you'll need for

programming the chip.

Load Programs with FTDI

![[Circuit for Atmega328 on breadboard with FTDI friend]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/arduino/bare-atmega-breadboard-ftdi_bb.jpg) An FTDI board is a little trickier to wire than an ISP, but it's

less risky because it loads the code the same way an Arduino would,

so you don't overwrite the bootloader and you

can still put your chip back into an Arduino if things go wrong.

So let's start with FTDI.

An FTDI board is a little trickier to wire than an ISP, but it's

less risky because it loads the code the same way an Arduino would,

so you don't overwrite the bootloader and you

can still put your chip back into an Arduino if things go wrong.

So let's start with FTDI.

I use an

Adafruit "FTDI Friend", but there are lots of similar

FTDI boards from Sparkfun

and other vendors. They have six outputs,

but you'll need only five of those. Referring to your Atmega pinout,

wire up power, ground, TX, and RX. For some FTDI boards you may need

pullup resistors on the TX and RX lines; I didn't need them.

Now you have four pins connected.

Wiring the reset line is more complicated because it requires a

0.1μF capacitor. A lot of tutorials don't mention the capacitor,

but it didn't work for me without one.

Connect from RTS on the FTDI board, through the

0.1μF cap, to the RST line.

A 0.1μF capacitor is an electrolytic cap with a positive and a

negative lead, but the few online tutorials that even mention the

capacitor don't bother to say which side is whick. I connected the

FTDI friend to the cap's negative lead, and the positive lead to the

Atmega chip, and it worked.

You may also need a pullup on that RST/RTS line: a resistor

around 10kΩ from the RST pin 1 of the atmega chip to the 5v power line.

Note: the Fritzing diagram here shows pullup resistors on RST, TX

and RX. You may not need any of them.

Incidentally, RST stands for "reset", while RTS stands for "Ready To

Send"; they're not meant as anagrams of each other. The remaining pin

on the FTDI friend, CTS, is "Clear To Send" and isn't needed for an

Arduino.

Once the wiring is ready, plug in the FTDI board, check to make sure

Port is set to whatever port the FTDI board registered,

and try uploading a program as if you were uploading to a normal Arduino Uno.

And cross your fingers. If it doesn't work, try fiddling with pullups

and capacitor values.

Load Programs with an ISP

![[Circuit for Atmega328 on breadboard with ISP]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/arduino/bare-atmega-breadboard-isp_bb.jpg) An In-System Programmer, or ISP, writes programs straight to the chip,

bypassing (and overwriting) the Arduino bootloader. You can also use

an ISP to burn a new bootloader and reprogram the fuses on your

Arduino, to change parameters like the clock rate. (More on that in Part 2.)

An In-System Programmer, or ISP, writes programs straight to the chip,

bypassing (and overwriting) the Arduino bootloader. You can also use

an ISP to burn a new bootloader and reprogram the fuses on your

Arduino, to change parameters like the clock rate. (More on that in Part 2.)

You can use an

Arduino as an ISP, but it's somewhat unreliable and

prone to unexplained errors. A dedicated ISP isn't expensive, is

easier to wire and is more likely to work. A common type of ISP is

called a "USBtinyISP", and you can buy one from vendors like

Sparkfun or

Adafruit,

or search for usbtinyisp on sites like ebay or aliexpress.

Update: I've been curious about this flakiness: why does "Arduino as ISP"

work fine for some people and utterly fail for others? One person I asked

thought it had to do with the way Arduinos reset the RESET line whenever

the serial port is opened: so RESET gets toggled at the wrong time as

the bootloader code is being transferred.

An alternate method that may get around this is

Gammon Forum's

Atmega bootloader programmer, which includes the bootloader bits

as part of the code so it doesn't need to re-open the serial port.

Someone else says a 10 uF capacitor between reset and ground should

prevent that from happening; and another person says it should be a

100nF capacitor between RST on the programmer and RST on the AVR-chip

plus a 10k pullup resistor,

Most Arduino-as-ISP tutorials, including the official ones on arduino.cc,

don't mention either capacitors or pullups,

so that may explain why the method works for some people and not others.

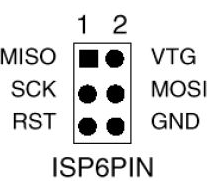

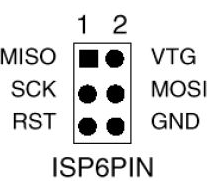

ISPs typically use a six-pin connector (2x3). It's not always easy to

figure out which end is which, so use a multimeter in continuity mode

to figure out which pin is ground. Once you're sure, mark your connector

so you'll know which pin is pin 1 (MISO, the pin opposite ground).

ISPs typically use a six-pin connector (2x3). It's not always easy to

figure out which end is which, so use a multimeter in continuity mode

to figure out which pin is ground. Once you're sure, mark your connector

so you'll know which pin is pin 1 (MISO, the pin opposite ground).

Once you have your ISP pins straight, refer to your handy-dandy

Atmega328 pinout and connect power, ground, MOSI, MISO, SCK, and RST

to the appropriate Atmega pins.

All wired up? In the Arduino IDE, set Programmer to your ISP,

for instance, USBtinyISP or Arduino as ISP

Then use the Upload button to upload sketches.

If you prefer Arduino-mk instead of the IDE, add this to your Makefile:

ISP_PROG = usbtiny

(or whatever ISP you're using). Then type

make ispload

instead of

make upload

Once you have your FTDI or ISP working, then you can think about making

an even simpler circuit -- without the external clock and its associated

capacitors. But there are a couple of additional tricks to that.

Stay tuned for Part 2.

Tags: hardware, arduino, maker

[

15:44 Dec 09, 2017

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Mon, 04 Dec 2017

![[Raspberry Pi Zero W with LED]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/pi-no-headers.jpg) Are you interested in all things Raspberry Pi, or just curious about them?

Come join like-minded people this Thursday at 7pm for the inaugural meeting

of the Los Alamos Raspberry Pi club!

Are you interested in all things Raspberry Pi, or just curious about them?

Come join like-minded people this Thursday at 7pm for the inaugural meeting

of the Los Alamos Raspberry Pi club!

At Los Alamos Makers,

we've had the Coder Dojo for Teens going on for over a year now,

but there haven't been any comparable programs that welcomes adults.

Pi club is open to all ages.

The format will be similar to Coder Dojo: no lectures or formal

presentations, just a bunch of people with similar interests.

Bring a project you're working on, see what other people are working

on, ask questions, answer questions, trade ideas and share knowledge.

Bring your own Pi if you like, or try out one of the Pi 3 workstations

Los Alamos Makers has set up. (If you use one of the workstations there,

I recommend bringing a USB stick so you can save your work to take home.)

Although the group is officially for Raspberry Pi hacking, I'm sure

many attendees will interested in Arduino or other microcontrollers, or

Beaglebones or other tiny Linux computers; conversation and projects

along those lines will be welcome.

Beginners are welcome too. You don't have to own a Pi, know a resistor

from a capacitor, or know anything about programming. I've been asked

a few times about where an adult can learn to program. The Raspberry Pi

was originally introduced as a fun way to teach schoolchildren to

program computers, and it includes programming resources suitable to

all ages and abilities. If you want to learn programming on your own

laptop rather than a Raspberry Pi, we won't turn you away.

Raspberry Pi Club:

Thursdays, 7pm, at Los Alamos Makers, 3540 Orange Street (the old PEEC

location), Suite LV1 (the farthest door from the parking lot -- look

for the "elevated walkway" painted outside the door).

There's a Facebook event:

Raspberry Pi club

on Facebook. We have meetings scheduled for the next few Thursdays:

December 7, 14, and 21, and after that we'll decide based on interest.

Tags: maker, hardware, raspberry pi, programming, maker

[

10:44 Dec 04, 2017

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Wed, 29 Nov 2017

Having written a basic blink program in C for

my

ATtiny85 with a USBtinyISP (Part 1), I wanted to use it to control other

types of hardware. That meant I wanted to be able to use Arduino libraries.

The Arduino IDE

I normally use Makefiles, but the Arduino IDE is much better supported

so I tried that first. I followed the steps at

High-Low

Tech: Programming an ATtiny w/ Arduino 1.6 (or 1.0).

But the short summary is:

- Run the Arduino IDE

- File->Preferences

- In "Additional Boards Manager" near the bottom, paste this:

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/damellis/attiny/ide-1.6.x-boards-manager/package_damellis_attiny_index.json

and click OK

- Tools->Boards->Board Manager...

- Find the ATTiny entry, click on it, and click Install

- Back in the main Arduino IDE, Tools->Boards should now havea

couple of Attiny entries. Choose the one that corresponds to your

ATTiny; then, under Processor, narrow it down further.

In

Tools->Programmer, choose the programmer you're using

(for example,

USBtinyISP).

Now you should be able to Verify and Upload a blink sketch

just like you would to a regular Arduino, subject to the pin limitations

of the ATTiny.

That worked for blink. But it didn't work when I started adding libraries.

Since the command-line was what I really cared about, I moved on rather

than worrying about libraries just yet.

ATtiny with Arduino-Makefile

For most of my Arduino development I use an excellent package called

Arduino-Makefile.

There's a Debian package called arduino-mk that works fine for normal

Arduinos, but for ATtiny, there have been changes, so use the version

from git.

A minimal blink Makefile looks like this:

BOARD_TAG = uno

include /usr/share/arduino/Arduino.mk

It assumes that if you're in a directory called blink, it

should compile a file called blink.ino. It will also build

any additional .cpp files it finds there. make upload

uploads the code to a normal Arduino.

With Attiny it gets quite a bit more complicated.

The key is that you have to specify an alternate core:

ALTERNATE_CORE = ATTinyCore

But there are lots of different ATtiny cores, they're all different,

and they each need a different set of specifiers like BOARD_TAG in

the Makefile. Arduino-Makefile comes with an example, but it isn't

very useful since it doesn't say where to get the cores that correspond

with the various samples. I ended up filing a documentation bug and

exchanging some back-and-forth with the maintainer of the package,

Simon John, and here's what I learned.

First: as I mentioned earlier, you should use the latest git version

of Arduino-Makefile. The version in Debian is a little older and some

things have changed; while the older version can be made to work with

ATtiny, the recipes will be different from the ones here.

Second, the recipes for each core will be different depending on which

version of the Arduino software you're using. Simon

says he sticks to version 1.0.5 when he uses ATtinys, because newer

versions don't work as well. That may be smart (certainly he has a lot

more experience than I do), but I'm always hesitant to rely on

software that old, so I wanted to get things working with the latest

Arduino, 1.8.5, if i could, so that's what the recipes here will

reflect.

Third, as mentioned in Part 1, clock rate should be 1MHz, not 8MHz

as you'll see in a lot of web examples, so:

F_CPU = 1000000L

Fourth, uploading sketches. As mentioned in the last article, I'm using

a USBtinyISP. For that, I use ISP_PROG = usbtiny and

sketches are uploaded by typing make ispload rather than

the usual make upload. change that if you're usinga

different programmer.

With those preliminaries over:

I ended up getting two different cores working,

and there were two that didn't work.

Install the cores in subdirectories in

your ~/sketchbook/hardware directory. You can have multiple

cores installed at once if you want to test different cores.

Here are the recipes.

CodingBadly's arduino-tiny

This is the core that Simon says he prefers, so it's the one I'm going

to use as my default. It's at

https://github.com/Coding-Badly/arduino-tiny.git,

and also a version on Google Code. (Neither one has been updated since 2013.)

git clone it into your sketchbook/hardware.

Then either cp 'Prospective Boards.txt' boards.txt

or create a new boards.txt and copy from 'Prospective Boards.txt'

all the boards you're interested in (for instance, all the attiny85

definitions if attiny85 is the only attiny board you have).

Then your Makefile should look something like this:

ARDUINO_DIR = /path/to/arduino-1.8.5

BOARD_TAG = attiny85at8

ALTERNATE_CORE = tiny

F_CPU = 1000000L

ISP_PROG = usbtiny

include /path/to/Arduino-Makefile/Arduino.mk

If your Arduino software is installed in /usr/share/arduino you can

omit the first line.

Now copy blink.ino -- of course, you'll have to change pin 13

to be something between 1 and 6 since that's how many pins an ATtiny

has -- and try make and make ispload.

SpenceKonde's ATTinyCore

This core is at https://github.com/SpenceKonde/ATTinyCore.git.

I didn't need to copy boards.txt or make any other changes,

just clone it under sketches/hardware and then use this Makefile:

ARDUINO_DIR = /path/to/arduino-1.8.5

ALTERNATE_CORE = ATTinyCore

BOARD_TAG = attinyx5

BOARD_SUB = 85

F_CPU = 1000000L

ISP_PROG = usbtiny

include /path/to/Arduino-Makefile/Arduino.mk

Non-working Cores

There are plenty of other ATtiny cores around. Here are two that

apparently worked once, but I couldn't get them working with the

current version of the tools. I'll omit links to them to try to

reduce the probability of search engines linking to them rather

than to the more up-to-date cores.

Damellis's attiny (you may see this referred to as HLT after the

domain name, "Highlowtech"), on GitHub as

damellis/attiny,

was the first core I got working with Debian's older version of

arduino-mk and Arduino 1.8.4. But when I upgraded to the latest

Arduino-Makefile and Arduino 1.8.5, it no longer worked. Ironic since

an older version of it was the one used in most of the tutorials I

found for using ATtiny with the Arduino IDE.

Simon says this core is buggy: in particular, there are problems with

software PWM.

I also tried rexxar-tc's arduino-tiny.core2 (also on GitHub).

I couldn't get it to work with any of the Makefile or Arduino

versions I tried, though it may have worked with Arduino 1.0.

With two working cores, I can get an LED to blink.

But libraries are the point of using the Arduino framework ...

and as I tried to move beyond blink.ino, I found that

not all Arduino libraries work with ATtiny.

In particular, Wire, used for protocols like I2C to talk to all

kinds of useful chips, doesn't work without substantial revisions.

But that's a whole separate topic. Stay tuned.

Tags: hardware, arduino, programming, maker

[

19:06 Nov 29, 2017

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Thu, 02 Nov 2017

![[ATtiny85 and USBtinyISP programmer]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/hardware/img_1889sm.jpg) Arduinos are great for prototyping, but for a small, low-power,

cheap and simple design, an ATtiny chip seems like just the ticket.

For just a few dollars you can do most of what you could with an

Arduino and use a lot of the same code, as long as you can make do

with a little less memory and fewer pins.

Arduinos are great for prototyping, but for a small, low-power,

cheap and simple design, an ATtiny chip seems like just the ticket.

For just a few dollars you can do most of what you could with an

Arduino and use a lot of the same code, as long as you can make do

with a little less memory and fewer pins.

I've been wanting to try them, and recently I ordered a few ATtiny85 chips.

There are quite a few ways to program them. You can buy programmers

specifically intended for an ATtiny, but I already had a USBtinyISP,

a chip used to program Arduino bootloaders, so that's what I'll

discuss here.

Wiring to the USBtinyISP

![[ATtiny85 and USBtinyISP wiring]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/hardware/attiny-usbtinyISP_bb.jpg) The best reference I found on wiring was

Using USBTinyISP to program ATTiny45 and ATTiny85.

That's pretty clear, but I made my own Fritzing diagram, with colors,

so it'll be easy to reconstruct it next time I need it.

The colors I used:

The best reference I found on wiring was

Using USBTinyISP to program ATTiny45 and ATTiny85.

That's pretty clear, but I made my own Fritzing diagram, with colors,

so it'll be easy to reconstruct it next time I need it.

The colors I used:

| MISO

| yellow

| VCC | red

|

| SCK

| white

| MOSI | green

|

| RESET

| orange

or red/black

| GND | black

|

Programming the ATtiny in C

I found a couple of blink examples at

electronut.in,

Getting Started with ATtiny AVR programming,

and in a Stack Exchange thread,

How

to program an AVR chip in Linux

Here's some basic blink code:

#include <avr/io.h>

#include <util/delay.h>

int main (void)

{

// Set Data Direction to output on port B, pins 2 and 3:

DDRB = 0b00001000;

while (1) {

// set PB3 high

PORTB = 0b00001000;

_delay_ms(500);

// set PB3 low

PORTB = 0b00000000;

_delay_ms(500);

}

return 1;

}

Then you need a Makefile. I started with the one linked from the electronut

page above. Modify it if you're using a programmer other than a USBtinyISP.

make builds the program, and make install

loads it to the ATtiny. And, incredibly, my light started blinking,

the first time!

![[ATtiny85 pinout]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/hardware/attiny85-pinout.jpg) Encouraged, I added another LED to make sure I understood.

The ATtiny85 has six pins you can use (the other two are power and ground).

The pin numbers correspond to the bits in DDRB and PORTB:

my LED was on PB3. I added another LED on PB2 and made it alternate

with the first one:

Encouraged, I added another LED to make sure I understood.

The ATtiny85 has six pins you can use (the other two are power and ground).

The pin numbers correspond to the bits in DDRB and PORTB:

my LED was on PB3. I added another LED on PB2 and made it alternate

with the first one:

DDRB = 0b00001100;

[ ... ]

// set PB3 high, PB2 low

PORTB = 0b00001000;

_delay_ms(500);

// set PB3 low, PB2 high

PORTB = 0b00000100;

_delay_ms(500);

Timing Woes

But wait -- not everything was rosy. I was calling _delay_ms(500),

but it was waiting a lot longer than half a second between flashes.

What was wrong?

For some reason, a lot of ATtiny sample code on the web assumes the

chip is running at 8MHz. The chip's internal oscillator is indeed 8MHz

(though you can also run it with an external crystal at various

speeds) -- but its default mode uses that oscillator in "divide by

eight" mode, meaning its actual clock rate is 1MHz. But Makefiles

you'll find on the web don't take that into account (maybe because

they're all copied from the same original source). So, for instance,

the Makefile I got from electronut has

CLOCK = 8000000

If I changed that to

CLOCK = 1000000

now my delays were proper milliseconds, as I'd specified.

Here's my working

attiny85

blink Makefile.

In case you're curious about clock rate, it's specified by what are

called fuses, which sound permanent but aren't: they hold their

values when the chip loses power, but you can set them over and over.

You can read the current fuse settings like this:

avrdude -c usbtiny -p attiny85 -U lfuse:r:-:i -v

which should print something like this:

avrdude: safemode: hfuse reads as DF

avrdude: safemode: efuse reads as FF

avrdude: safemode: Fuses OK (E:FF, H:DF, L:62)

To figure out what that means, go to the

Fuse calculator,

scroll down to Current settings and enter the three values

you got from avrdude (E, H and L correspond to Extended, High and Low).

Then scroll up to Feature configuration

to see what the fuse settings correspond to.

In my case it was

Int. RC Osc. 8 Mhz; Start-up time PWRDWN/RESET; 6CK/14CK+

64ms; [CKSEL=1011 SUT=10]; default value

and Divide clock by 8 internally; [CKDIV8=0] was checked.

More on ports and pins

There's more info on ATtiny ports in

ATTiny

Port Manipulation (Part 1): PinMode() and DigitalWrite()

Nobody seems to have written much about AVR/ATTINY

programming in general. Symbols like PORTB and

functions like _delay_ms() come from files in

/usr/lib/avr/include/, at least on my Debian system.

There's not much there, so if you want library functions to handle

nontrivial hardware, you'll have to write them or find them somewhere else.

As for understanding pins, you're supposed to go to the datasheet and read it

through, all 234 pages. Hint: for understanding basics of reading from and

writing to ports, speed forward to section 10, I/O Ports.

A short excerpt from that section:

Three I/O memory address locations are allocated for each port, one

each for the Data Register - PORTx, Data Direction Register - DDRx,

and the Port Input Pins - PINx. The Port Input Pins I/O location is

read only, while the Data Register and the Data Direction Register are

read/write. However, writing a logic one to a bit in the PINx

Register, (comma sic) will result in a toggle in the

corresponding Data Register. In addition, the Pull-up Disable - PUD

bit in MCUCR disables the pull-up function for all pins in all ports

when set.

There's also some interesting information there about built-in pull-up

resistors and how to activate or deactivate them.

That's helpful, but here's the part I wish they'd said:

PORTB (along with DDRB and PINB) represents all six pins. (Why B? Is

there a PORTA? Not as far as I can tell; at least, no PORTA is

mentioned in the datasheet.) There are six output pins, corresponding

to the six pins on the chip that are not power or ground. Set the bits

in DDRB and PORTB to correspond to the pins you want to set. So if you

want to use pins 0 through 3 for output, do this:

DDRB = 0b00001111;

If you want to set logical pins 1 and 3 (corresponding to pins 6 and 2

on the chip) high, and the rest of the pins low, do this:

PORTB = 0b00001010;

To read from pins, use PINB.

In addition to basic functionality, all the pins have specialized

uses, like timers, SPI, ADC and even temperature measurement (see the

diagram above). The datasheet goes into more detail about how to get

into some of those specialized modes.

But a lot of those specialties are easier to deal with using

libraries. And there are a lot more libraries available for the Arduino

C++ environment than there are for a bare ATtiny using C.

So the next step is to program the ATtiny using Arduino ...

which deserves its own article.

Tags: hardware, arduino, programming, maker

[

18:01 Nov 02, 2017

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Thu, 28 Sep 2017

Someone at our makerspace found a fun Halloween project we could do

at Coder Dojo: a

motion

sensing pumpkin that laughs evilly when anyone comes near.

Great! I've worked with both PIR sensors and ping rangefinders,

and it sounded like a fun project to mentor. I did suggest, however,

that these days a Raspberry Pi Zero W is cheaper than an Arduino, and

playing sounds on it ought to be easier since you have frameworks like

ALSA and pygame to work with.

The key phrase is "ought to be easier".

There's a catch: the Pi Zero and Zero W don't

have an audio output jack like their larger cousins. It's possible to

get analog audio output from two GPIO pins (use the term "PWM output"

for web searches), but there's a lot of noise. Larger Pis have a built-in

low-pass filter to screen out the noise, but on a Pi Zero you have to

add a low-pass filter. Of course, you can buy HATs for Pi Zeros that

add a sound card, but if you're not super picky about audio quality,

you can make your own low-pass filter out of two resistors and two capacitors

per channel (multiply by two if you want both the left and right channels).

There are lots of tutorials scattered around the web about how to add

audio to a Pi Zero, but I found a lot of them confusing; e.g.

Adafruit's

tutorial on Pi Zero sound has three different ways to edit the

system files, and doesn't specify things like the values of the

resistors and capacitors in the circuit diagram (hint: it's clearer if you

download the Fritzing file, run Fritzing and click on each resistor).

There's a clearer diagram in

Sudomod Forums:

PWM Audio Guide, but I didn't find that until after I'd made my own,

so here's mine.

Parts list:

- 2 x 270 Ω resistor

- 2 x 150 Ω resistor

- 2 x 10 nF or 33nF capacitor

- 2 x 1μF electrolytic capacitor

- 3.5mm headphone jack, or whatever connection you want to use to

your speakers

And here's how to wire it:

![[Adding audio to the Raspberry Pi Zero]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/pi-zero-audio_bb.jpg)

(Fritzing file, pi-zero-audio.fzz.)

This wiring assumes you're using pins 13 and 18 for the left and right

channels. You'll need to configure your Pi to use those pins.

Add this to /boot/config.txt:

dtoverlay=pwm-2chan,pin=18,func=2,pin2=13,func2=4

Testing

Once you build your circuit up, you need to test it.

Plug in your speaker or headphones, then make sure you can play

anything at all:

aplay /usr/share/sounds/alsa/Front_Center.wav

If you need to adjust the volume, run alsamixer and

use the up and down arrow keys to adjust volume. You'll have to press

up or down several times before the bargraph actually shows a change,

so don't despair if your first press does nothing.

That should play in both channels. Next you'll probably be curious

whether stereo is actually working. Curiously, none of the tutorials

address how to test this. If you ls /usr/share/sounds/alsa/

you'll see names like Front_Left.wav, which might lead you to

believe that aplay /usr/share/sounds/alsa/Front_Left.wav

might play only on the left. Not so: it's a recording of a voice

saying "Front left" in both channels. Very confusing!

Of course, you can copy a music file to your Pi, play it (omxplayer

is a nice commandline player that's installed by default and handles

MP3) and see if it's in stereo. But the best way I found to test

audio channels is this:

speaker-test -t wav -c 2

That will play those ALSA voices in the correct channel, alternating

between left and right.

(MythTV has a good

Overview

of how to use speaker-test.

Not loud enough?

I found the volume plenty loud via earbuds, but if you're targeting

something like a Halloween pumpkin, you might need more volume.

The easy way is to use an amplified speaker (if you don't mind

putting your nice amplified speaker amidst the yucky pumpkin guts),

but you can also build a simple amplifier.

Here's one that looks good, but I haven't built one yet:

One Transistor Audio for Pi Zero W

Of course, if you want better sound quality, there are various places

that sell HATs with a sound chip and line or headphone out.

Tags: raspberry pi, electronics, audio, linux, hardware, maker

[

15:49 Sep 28, 2017

More hardware |

permalink to this entry |

]

Thu, 10 Aug 2017

![[Curved rod barn-door mount]](http://shallowsky.com/blog/images/barndoor/img_1410sm.jpg) I've been meaning forever to try making a "barn door" tracking mount.

Used mainly for long-exposure wide-field astrophotography, the barn door

mount, invented in 1975, is basically two pieces of wood with a hinge.

The bottom board mounts on a tripod and is pointed toward the North Star;

"opening" the hinge causes the top board to follow the motion of the

sky, like an equatorial telescope mount. A threaded rod and a nut

control the angle of the "door", and you turn the nut manually every

so often. Of course, you can also drive it with a motor.

I've been meaning forever to try making a "barn door" tracking mount.

Used mainly for long-exposure wide-field astrophotography, the barn door

mount, invented in 1975, is basically two pieces of wood with a hinge.

The bottom board mounts on a tripod and is pointed toward the North Star;

"opening" the hinge causes the top board to follow the motion of the

sky, like an equatorial telescope mount. A threaded rod and a nut

control the angle of the "door", and you turn the nut manually every

so often. Of course, you can also drive it with a motor.

We're off to view the eclipse in a couple of weeks.

Since it's my first total eclipse, my plan is to de-emphasize

photography: especially during totality, I want to experience the

eclipse, not miss it because my eyes are glued to cameras and timers

and other equipment. But I still want to take photos every so often.

Constantly adjusting a tripod to keep the sun in frame is another

hassle that might keep my attention away from the eclipse. But real

equatorial mounts are heavy and a time consuming to set up;

since I don't know how crowded the area will be, I wasn't

planning to take one. Maybe a barn door would solve that problem.

Perhaps more useful, it would mean that my sun photos would all be

rotated approximately the right amount, in case I wanted to make an

animation. I've taken photos of lunar and partial solar eclipses, but

stringing them together into an animation turned out to be too much

hassle because of the need to rotate and position each image.

I've known about barn-door mounts since I was a kid, and I knew the

basic theory, but I'd never paid much attention to the details. When I

searched the web, it sounded complicated -- it turned out there are

many types that require completely different construction techniques.

The best place to start (I found out after wasting a lot of time on

other sites) is the

Wikipedia

article on "Barn door tracker", which gives a wonderfully clear

overview, with photos, of the various types. I had originally been

planning a simple tangent or isosceles type; but when I read

construction articles, it seemed that those seemingly simple types

might not be so simple to build: the angle between the threaded rod

and the boards is always changing, so you need some kind of a pivot.

Designing the pivot looked tricky. Meanwhile, the pages I found on

curved-rod mounts all insisted that bending the rod was easy, no

trouble at all. I decided to try a curved-rod mount first.